Neith: A Magazine of Literature, Science, Art, Philosophy, Jurisprudence, Criticism was a literary and cultural magazine edited by Abraham Beverly Walker and published in Saint John, New Brunswick. It ran for five issues between February 1903 and January 1904 and is widely considered to have been the first Black literary magazine in Canada. Its stated purpose, expressed in the first issue's editorial, was "to set people thinking, to extirpate erroneous ideas, to advance the spirit of freedom, to stir up a feeling of brothership among all men, and to spread Christian civilization throughout Africa" ("Prefatory" 1). Situated at the intersection of competing discourses—Canadian nationalism, North-American Black nationalism, pan-Africanism, and British imperialism—Neith sought to be international in scope and significance, even as it was rooted in, and shaped by, its specific local and national contexts. At once giving a voice to Black intellectuals within the Maritime Provinces of Canada and committed to a pan-African Black nationalism, Neith challenged the homogenous and exclusionary representations of regional and national identity being promulgated in local and national magazines at the turn of the twentieth century.

(Source: Special Collections, Acadia University Library, Acadia University, Wolfville NS.)

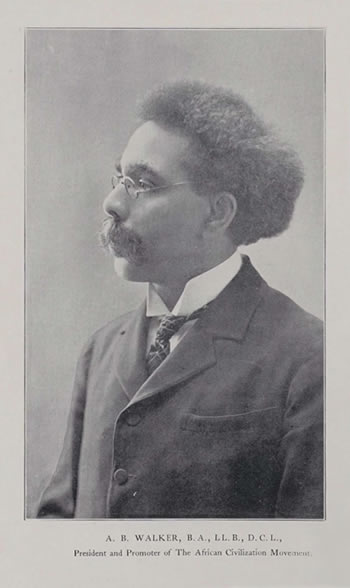

In nearly every respect, Neith resulted from the commitment and dedication of its editor, Abraham Beverly Walker (see Fig. 1). A lawyer, journalist, and activist from Belleisle Creek, New Brunswick, Walker received his Bachelor of Laws from National University in Washington, DC and was admitted as an attorney in New Brunswick in 1881. He was called to the bar in 1882, making him the first Canadian-born Black barrister in Canada. After working as a court reporter, Walker emigrated to the United States for two years before returning to attend the newly established Saint John Law School (now the University of New Brunswick faculty of law) in 1892. Legal historian Barry Cahill documents the difficulties Walker faced as a Black barrister in Victorian Canada. Bureaucratic and public racism, a "white-chauvinist culture," and a relatively small Black population prevented Walker from maintaining a successful law practice (Cahill 376).

More successful was Walker's extra-legal activism. Throughout his career, Walker was an untiring essayist, lecturer, and community activist, publishing letters and articles in local, regional, and American papers and lecturing across Canada and in the United States on "the Negro Problem." Two of these lectures were later expanded and published as The Negro Problem; or, the Philosophy of Race Development from a Canadian Viewpoint (1890) and Victoria the Good: The Great and Glorious Mother of Liberty, Justice, Right, Truth and Equity, of Modern Civilization; and the Mightiest Force for Righteousness in the World since the Time of Jesus: A Lecture (1901). His greatest achievement as a writer and journalist, however, came when he established Neith in 1903. Walker not only founded, edited, and promoted the magazine, but also contributed the vast majority of the magazine's content, authoring more than one hundred short essays, editorials, and reviews for the magazine during its short run. For Walker, Neith was to be a vehicle for change and racial advancement, and at the core of his editorial programme was a belief in the power of civil discourse coupled with creative expression to effect social reform.

The first issue of Neith appeared in Saint John in February 1903. It was printed by Paterson Publishing & Co. in super octavo format on medium weight printing paper with a matte finish for covers and a gloss finish for images. Ranging from fifty-four pages (no. 5) to seventy-six pages (no. 3), and averaging sixty pages per issue, the magazine was an expensively produced illustrated monthly. The first issue is exemplary of Walker's editorial direction: running to seventy-two pages, the issue consists of prefatory remarks followed by eleven unsigned short essays, five medium-length essays (including the first part of Walker's serialized "The Negro Problem, and How to Solve it"), four signed longer essays, three poems, literary notes (comprising brief essays, commentary, and reviews), and editorial announcements. In addition to Walker, six contributors are identified in the first issue. The essays treat a wide array of subjects, from the Canadian economy and British politics to the works of Émile Zola and Henrik Ibsen. Also included were reviews of the latest poetry chapbooks of Canadian poets Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman. Despite the magazine's eclecticism, Walker's forceful polemics on racial advancement and Black nationalism were central to every issue.

(Source: Neith vol. 1, no. 1.)

Moreover, the visual aesthetic of the magazine was clearly oriented toward Walker's editorial mission. Printed in dark blue, the cover of the first issue features an illustration of Neith, "an Ethiopic divinity," holding a scepter in her left hand and grasping a bolt of lightning in her right (see Fig. 2). These bolts emanate from the title, centred just above, which is drawn in capitalized sans-serif font. Surrounding this image is a trefoil arch featuring an image of the Great Sphinx in the upper left and of the Great Pyramids in the upper right. At top-center is an inverted pentagram. Along the bottom, at the base of the columns that frame either side, is the Latin inscription Ecripuit cælo fulmen sceptrumque tyrannis ("he snatched the lightning from heaven and the sceptre from tyrants"). The "Editorial Announcements" inform the reader that Neith "was worshipped in Meroe, Egypt, and Carthage. She stood for Liberty, Wisdom, and Eternal Justice, and presided over the thunder and the tempest" (59). The same design, in varying colours, would appear on the cover of all five issues. This created a visual aesthetic that mirrors the magazine's textual contents, and which evokes the Ethiopianism then current among African and African-American intellectuals—including magazine editors such as W.E.B Du Bois and, later, Marcus Garvey.

The magazine's visual aesthetic thus emphasizes Walker's engagement with transnational Black intellectual and print-cultural currents, including political-cultural touchstones such as Booker T. Washington's "Atlanta Compromise" (1895) and Up From Slavery (1901), and Du Bois' The Souls of Black Folk (1903). Another key African-American intellectual who significantly influenced Walker and the editorial programme of Neith was Rev. Henry McNeil Turner, former Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and editor of African-American newspaper The Voice of the People (1901-1905). In Neith, Turner is both listed as a member of the editorial board and cited by Walker as an ally in the cause for emigration to Africa.

Similarly, Neith finds its closest analogues among twentieth-century African-American magazines. These include magazines that resemble Neith in form and content, such as Walter Wallace's Washington-friendly and accommodationist-oriented[1] Coloured American Magazine (Atlanta, 1900-09); J. Max Barber's increasingly anti-accommodationist Voice of the Negro (Atlanta, 1904-05); and Du Bois' short-lived The Moon Illustrated (Memphis 1905-06) and much longer-lasting The Crisis (Baltimore 1910-). These magazines, not exclusively Black, but focussing primarily on African-American concerns, were political and cultural periodicals with a strong literary focus. In terms of the specific political enterprise to which it was committed, however, Neith was more closely aligned with newspapers like Henry McNeal Turner's The Voice of the People (1901-04) and thus anticipates, over a decade later, Marcus Garvey's Negro World (New York 1918-33). Both of these periodicals served as vehicles for the promotion of their editors' respective back-to-Africa schemes—Turner's International Migration Society and the Black Star Line operated by Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association.

In addition to foreshadowing the iconography employed by major African-American magazines like The Crisis, the cover, imagery, and format of Neith reinforced the magazine's textual content. When taken in conjunction with Walker's explanatory note, the iconography and symbolism incorporated in the cover are suggestive of those key conceptual orientations that Walker engaged within the magazine: Afrocentrism, Ethiopianism, imperialism, the veneration of African antiquity, racial equality, and anti-Americanism. Articles on these themes consistently accounted for just over one-half of each issue. Accordingly, the contents of the first issue of Neith can be roughly divided into two parts. The first and more substantial part contains short and medium-length essays by Walker on a range of topics concerning racial politics, civil rights, and British colonial affairs. The second half includes articles, poems, and book-reviews by several other contributors—including prominent Maritime intellectuals like W.O. Raymond, Francis Partridge, and H.A. McKeown—on varied subjects that are largely divorced from Walker's civil-rights articles. None of the short articles are signed, but the similarity of focus and the forceful, oratorical prose in which they are written suggest they are the product of Walker's pen. And across these sixteen brief and medium-length essays, one can trace the contours of Walker's Black nationalist programme.

For Walker, the "Negro Problem" is a national problem, even though the "national culture" he envisions is premised on British cultural values. Thus, Walker is less concerned with defining a distinct Black cultural identity than with contesting the libel of racial inferiority, wherever and everywhere it exists. So it is that in "Negrophobes Should be Kept out of Africa," Walker does not oppose British colonialism and cultural imperialism in Africa per se, but rather the racial intolerance and inequality that is, for Walker, the contingent consequence of colonialism: "England's African policy should be to preserve, as far as possible, African territory for the Negroes and a class of white people who are manifestly and professedly friendly to the Negroes" (6). For Walker, racism is manifest not in the system of British imperialism itself, but in the impediments to racial equality in the colonies, in any "opposition to the development and civilization of the negroes" (6). Walker did, however, greatly value Black national sovereignty. In "Hayti and its Enemies," Walker addresses the political instability that characterized Haiti at the turn of the century, particularly after 1902 when the resignation of Haitian President Tirésias Simon Sam led to violent clashes between the supporters of Anténor Firmin and General Nord Alexis. Walker indicts the "negrophobes" who are "constantly finding fault with Hayti" (2). "These outbreaks of insurrection," he continues, "are not puzzling or surprising; in countries where the rulers possess all the learning and the masses all the illiteracy, the government is generally cruel and corrupt" (2). Here, Walker swiftly transitions from discussing the specific geopolitical situation in Haiti to broader reflections on pan-African sovereignty, defending Haiti as a model of Black self-determination. Such rhetorical gestures might evince a universalizing tendency in Walker's writing, but they also underwrite his pan-Africanist approach to nationalism.

However, it is his articles treating post-Reconstruction America, Jim Crow, and African-American politics that exhibit Walker's fiercest polemics against racial intolerance, on the one hand, and his deepest engagement with African-American intellectual currents, on the other. Walker's assessment of the situation in the United States is clearly expressed in his article "Tillmanism, or Mob Rule in the South." There, Walker declares that "[the] history of the South is a record of a series of crimes; awful crimes; crimes against God and man and religion; crimes so brutal, so heinous, so revolting, that it would be an unpardonable sin to express them in words" (18). Walker specifically targets the Southern United States, but the threat to African-American freedoms, rights, and their continuing existence as a people, is not confined to the South. Rather, the purpose of the article is to identify the growth and expansion of what Walker calls "misethioposis"—a term he coins to denote the unalterable, intransigent racial hatred that increasingly defines white America. Walker's pathologization of Southern racism, his attempt to give it "a definite form in pathology and nomenclature" (22), underpins his broader thesis: that racial intolerance in North America is an epidemic unimpeded by regional boundaries such as the Mason-Dixon line. The only solution, Walker maintains, is emigration, for which he outlines a scheme in his treatise, "The Negro Problem, and How to Solve it." In it, he critiques the accommodationism of Washington, promotes a civil-rights programme that parallels that of Du Bois, and finally advocates the colonization of Africa by educated, Anglophone members of the African diaspora.

The list of contributors, as well as the number of reviews the magazine garnered, suggest that Neith was widely read at the regional level and in some parts of the United States. The first issue received notice in nearly all of Saint John's eight newspapers as well as several regional papers and magazines. What is conspicuously missing from all but one of those reviews, however, is any mention of Neith's central role as a vehicle for Walker's Black nationalism, his numerous articles on racial equality and Black rights, and his proposed solution to the "Negro Problem." The situation is telling: as an impressively produced periodical that published essays and poetry by Saint John's leading intellectuals, Neith was lauded as a welcome addition to regional print culture; however, as a magazine dedicated, in Walker's words, to providing "a forum" for "those who are bleeding under the heel of despotism and caste," Neith seems to have been regarded as somewhat of an anachronism—addressing itself to what many white reviewers deemed bygone issues of racial injustice ("Prefatory" 1). This more typical, liberal response—simply ignoring the magazine's more polemical anti-racist content—played into common narratives of Canadian exceptionalism that represented Canada as a tolerant, inclusive, and colour-blind foil to the intolerant, violent, and racist United States.

There were, however, more explicitly and avowedly racist reactions to the magazine. The most notable of these was a review in The New Freeman, Saint John's Irish Catholic newspaper. There the reviewer wrote that "The editor [Walker], who deals with many issues, has all the proneness of his race for exaggerated thought and extravagant language" ("Neith" 7). Walker responded to that review in the third issue of Neith. Referring to the reviewer as "some ignorant, prejudiced, bigoted scribbler, who is unworthy of their race or their creed," Walker offers a figurative threat:

[Our] assailant is like the ass that a good-natured lion tried to be demonstrably neighborly with, and which mistook the lion's kindness and grace for a lack of courage and strength, and one day furiously jumped on the lion when he least expected it; of course, at the end of the fray there was a dead ass. ("The New Freeman" 63)

Clearly, Walker did not shy away from defending the magazine and its politics against racist attacks, challenging racist reviews and letters to the editor. Moreover, Walker never curtailed the space he was willing to devote to anti-racism. Despite his claim in the second issue that "neith is not a negro magazine, nor a Caucasian magazine, but a Canadian magazine inspired with Canadian principles of Liberty and Equity," Walker continued to prioritize articles focussed on racial equality and civil rights, with little regard for a specifically Canadian context ("Neith is Canadian" 1).

The final three issues, however, reveal the financial exigencies under which the magazine was published. In the second issue, Walker announced that Neith would no longer use italic type in order to be "utilitarian." Meanwhile, the issues consistently shrank, from 76 pages in the first issue to 56 and 52 pages in the fourth and fifth issues, respectively. Those issues were also printed on cheaper, light-weight pulp paper and contained fewer photographs. These changes clearly suggest financial distress. In fact, such difficulties were typical magazines in Canada at that time. At the turn of the century, Canadian magazine publishing was a financially risky undertaking and few Canadian magazines achieved the longevity of their American counterparts. Neith's financial precarity, however, was undoubtedly exacerbated by white readers' aversion to Walker's racial politics. In addition to trying to offset the costs of publication by altering the length and format of the magazine, Walker made an immense effort—including a marketing tour of Eastern Canada—to garner more subscribers and advertisers. Though Neith contained advertisements soliciting agents and advertisers in every issue, by the second issue Walker was already dedicating editorial space to appeals for support. Walker asked the Canadian public for both subscriptions and advertisements, insisting that "it is impossible for [Neith] to succeed unless the people of this country, almost to a unit, rally to our support" ("Editorial" 97). The appeal emphasizes the extent to which Neith was subject to public taste and (racial) discrimination. These were forces that Walker could resist only so far without losing his predominantly white contributors and readership and, in turn, the advertisers that financed the magazine. That Walker sustained Neith for over a year is a testament not only to Walker's skill as an editor, but also to his remarkable struggle to appeal to a broad readership without sacrificing his programme of racial advancement.

Intrepid though he was, Walker's efforts weren't enough. By the third issue, publication was three months behind schedule and the fifth issue appeared five months after the fourth. Walker begins the fifth and final issue with "A Special Note to Our Friends" in which he laments that the publication of Neith "is fraught with untold perplexities—perplexities, even at times, assuming a dramatic aspect" (199). He assures his readers, however, that "We are bound to win the goal, and nothing, except sickness and death, shall daunt us. NO SURRENDER, is our slogan" (199). The slogan was misplaced, but it is fitting that Neith ended the way it began, restating the magazine's pledge to "offer all opposition within our capacity to every form of evil or oppression" ("Editorial" 238). Through its entire run, Neith provided a forum in which Walker strove to articulate an Afrocentric, Black-nationalist programme that transcended its local, regional, and national contexts. To promote that programme to a Canadian readership, however, Walker had to first initiate an anti-racist dialogue in a city and nation where such discourse had been rendered all but invisible.

Neith was certainly not the first Black periodical in Canada; in many ways it continued the intellectual tradition once sustained in Black newspapers like The Voice of the Fugitive (Canada West and Ontario, 1851-1853) and The Provincial Freeman (Ontario, 1853-1860[?]). And yet, as critic Winfried Siemerling observes, "after the outpouring in the nineteenth century, a resurgence of black Canadian writing occurred only after the increase in Caribbean immigration from the mid-1950s on" (151). During the period of relative dearth in which Neith was published, white-Canadian antipathy precluded the very critique—transnational in scope but targeting regional and national racisms—that might have made Walker's politics more immediately relevant to a Black Canadian readership. Coupled with a perilous publishing market, these pressures undercut Walker's efforts from the outset.

Over its short run, then, Neith reveals the precarity of a magazine that sought to articulate a radical Black politics at a time when most Canadian periodicals were preoccupied with promoting Canadian nationalism and when no similar vehicle for anti-racist discourse existed in Canada. It was not in spite of this precarity, but, in part, because of it, that Walker engaged in a polemic that at once assimilates and transcends the nationalist and imperialist discourses that dominated the intellectual and cultural milieu of turn-of-the-century Canada.

It was likely the declining prominence of Saint John combined with its comparatively small Black population that led historian Robin Winks to claim that, "had Walker established his journal in Ontario … he might have succeeded" (401). Perhaps, but Neith's appearance in Saint John was not incidental. For while Saint John's white public may not have been receptive to Walker's radical Black nationalism, the city was nevertheless uniquely positioned as a site of cultural production and political contest. In the absence of a large commercial press industry, writers and intellectuals in Saint John relied disproportionately on periodicals for the dissemination of literature and ideas. At the turn of the century, Saint John maintained the same vigorous print culture that had placed it and its rival, Halifax, at the center of "British North America's burgeoning exercise of free expression" in the mid-nineteenth century (J. Walker 66). In 1903, the year Neith appeared, the city boasted eight newspapers, several monthly magazines, and twenty-two printing and publishing houses. Moreover, Saint John was home to a Black community with a strong tradition of activism and it constituted a key urban locus for Black literary and intellectual culture in the Maritime Provinces.

(Source: Neith vol. 1, no. 1, p. 53.)

Saint John's Black population declined through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The progressivism and social reform movements that characterized Victorian-era Saint John had few if any benefits for the city's Black population. The turn of the century saw increased job and housing discrimination, and most Black-owned businesses in Saint John either closed or sold out to whites because of the difficulty of obtaining capital. Nevertheless, the community persisted and developed a strong tradition of civil rights and community activism in the twentieth century. Such activism was exemplified by the organization of Saint John's Black community to protest the screening of D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation in 1916. Organized around St. Philip's African Methodist Episcopal Church, the community held protests, petitioned provincial censors, and eventually established a civil rights organization, the British Negro Protective Association. Walker was a part of this tradition of civil-rights activism, just as Neith was representative of Saint John's vibrant periodical culture. Neith, even more than Walker's other publications, must be read in relation to "the nexus of African-Canadian intellectuals in the Maritimes" in which the Canadian poet and critic George Elliott Clarke locates Walker (34). In fact, many of those "Africadian" intellectuals with whom Clarke assumes Walker to have been familiar—Rev. John Clay Coleman, Rev. Adam S. Green, James Robinson Johnston—either contributed to or were listed as editorial board members of Neith. Such inclusions not only confirm Walker's familiarity with leading Africadian intellectuals, but also suggest that the direction of influence may have been reciprocal.

After Neith folded in 1904, Walker dedicated his time and energy to promoting the African Civilization Movement (ACM), a back-to-Africa scheme that Walker had begun to develop in the 1890s and which was promoted in Neith through Walker's "The Negro Problem, and How to Solve it." The clearest statement of Walker's ACM is found in Message to the Public by Dr. A. B. Walker, president and promoter of the African Civilization Movement (Saint John, 1905). The imperialist plan would see educated, Anglicized members of the African diaspora in Britain, Canada, the United States, and the Caribbean colonize a "propitious part of British Africa" ("The Negro Problem" 181). Walker believed the colony could form the basis for an African Empire. The plan never came to fruition. Walker was in Ontario lecturing in promotion of the ACM when he came down with pulmonary tuberculosis, which led to his death in 1909.

Critical commentary unanimously stresses the historical significance of Neith: for Dean Irvine, "it deserves primary recognition as the first ‘little magazine' in Canada devoted to its Black population and the first edited by an African Canadian" (607); Dorothy Williams calls it "Canada's first Black literary magazine," "well-edited and intelligently conceived" (42); Merrill Distad notes that it was "short lived but highly distinguished" (127); and Barry Cahill observes that "Walker's cultural magazine, Neith, ‘the first African-Canadian literary periodical,' . . . merits a study in itself" (376). Despite such recognition, there exists no sustained critical treatment of Neith. Walker's career as a lawyer, journalist, and civil rights activist has, however, received variable attention in several studies, most notably W.A. Spray's The Blacks of New Brunswick, Robin Winks' "Negroes in the Maritimes: An Introductory Survey" and The Blacks in Canada, Barry Cahill's "First Things in Africadia; or, the Trauma of Being a Black Lawyer in Late Victorian Saint John," and Clarke's "Winking at Winks" in Directions Home: Approaches to African-Canadian Literature.

Spray's is one of the earliest histories to reference Walker, but his descriptions of Walker and Neith are brief and insubstantial. Cahill's article, by contrast, provides the most complete biography of Walker. Cahill describes the systemic and bureaucratic racism Walker confronted as the first Canadian-born Black barrister, as well as the politics and "white-chauvinist" culture that prevented Walker from maintaining a successful law practice in Saint John (376). Cahill, is squarely focussed on Walker's career in law (376). On the other hand, Winks' chapter "Source of Strength? —The Press" in The Blacks in Canada offers the most extensive treatment of Neith, but Winks' approach is marred by his refusal to deeply engage with the form and content of the magazine beyond cursory and superficial description. Nor does Winks treat Walker and his writing as a legitimate subject for critical analysis, opting instead to position Walker as a hopelessly naïve aberration in the history of Black-Canadian print culture, albeit one of "considerable talent" (398). Rejecting Winks' "usual professional sneering," Clarke provides the most thorough treatment of Walker's social, political, and philosophical thought (32). Clarke examines Walker's 1905 treatise Message to the Public and situates Walker within the broader fields of North-American and pan-African political-cultural thought. He identifies Walker as an Afrocentric "neo-British imperialist," whose Message to the Public "weds New World African imperialism to the globalist white supremacy articulated by backers of an 'Anglo-Saxon union' between Great Britain and the United States" (36).

In Neith the apparent contradiction between pan-African Black nationalism and neo-British imperialism appears not only within Walker's thought, but also between articles. The same "African diasporic imperialism" and "precocious fascism" that Clarke identifies in Walker's Message to the Public is in evidence in the pages of Neith, though Walker had not yet founded the African Civilization Movement of which he writes in the former (35). Neith can thus be seen as a sort of proving ground wherein Walker introduced, developed, and amended his positions on a range of political and cultural subjects—critical stances he would later consolidate in his other published works and lectures. A radical periodical produced on the periphery of nation and empire, Neith stands alone for having introduced into Canadian publishing the first Black literary magazine. But, more importantly, it sustained a radical Black politics in a nation where racial prejudice and Canadian exceptionalism all but occluded a generative discourse of race in mainstream print media.

Notes:

1. Accommodationism was a policy and approach to race relations in the United States advocated by some Southern Black leaders in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The strategy of accommodation encouraged African Americans to accept some discrimination and sacrifice potential civil rights, political equality, and higher education in exchange for economic and physical security. The most notable champion of accommodationism was Black leader, educator, and author Booker T. Washington. The policy of accommodation was first outlined in Washington's speech at the Atlanta Exposition of 1895, known as the "Atlanta Compromise."

Further Reading

Cahill, J B. "First Things in Africadia; Or, The Trauma of Being a Black Lawyer in Late Victorian Saint John.'" University of New Brunswick Law Journal, vol. 47, 1998, pp. 367–377.

---. "Walker, Abraham Beverly." Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, U of Toronto P, P De U Laval, 1994.

Clarke, George Elliott. "A.B. Walker and Anna Minerva Henderson: Two Afro-New Brunswick Responses to the ‘the Black Atlantic.'" Directions Home: Approaches to African-Canadian Literature. U of Toronto P, 2012, pp. 30-45.

---. "Africana Canadiana: A Select Bibliography of Literature by African-Canadian Authors, 1785–2001, in English, French, and Translation." Odysseys Home: Mapping African-Canadian Literature. U of Toronto P, 2002, pp. 339-448.

Distad, N. Merrill, and Linda M. Distad. "Canada." Periodicals of Queen Victoria's Empire: An Exploration. U of Toronto P, 1996, pp. 61-174.

Irvine, Dean. "Little Magazines in English Canada." The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, edited by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker, vol. 2, Oxford UP, 2009, pp. 602-628.

Jack, D.R. "Acadian Magazines." Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada 2nd s. 9 (1903): Sect. II, pp. 173-203.

Spray, W. A. The Blacks in New Brunswick. Brunswick Press, 1972.

Williams, Dorothy. "Print and Black Canadian Culture." History of the Book in Canada. 1840-1918, edited by Fiona A. Black et al., vol. 2, U of Toronto P, 2005, pp. 40-43.

Winks, Robin W. The Blacks in Canada: A History. 2nd ed., McGill-Queen's University Press, 2014.

---. "Negroes in the Maritimes: An Introductory Survey." Dalhousie Review, vol. 48, no. 4, 1968, pp. 453-71.

Works Cited

Cahill, J B. "First Things in Africadia; Or, The Trauma of Being a Black Lawyer in Late Victorian Saint John.'" University of New Brunswick Law Journal, vol. 47, 1998, pp. 367 – 377.

---. "Walker, Abraham Beverly." Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, U of Toronto P, P De U Laval, 1994.

Clarke, George Elliot. "A.B. Walker and Anna Minerva Henderson: Two Afro-New Brunswick Responses to the ‘the Black Atlantic.'" Directions Home: Approaches to African-Canadian Literature. U of Toronto P, 2012, pp. 30-45.

Distad, N. Merrill, and Linda M. Distad. "Canada." Periodicals of Queen Victoria's Empire: An Exploration. U of Toronto P, 1996, pp. 61-174.

Irvine, Dean. "Little Magazines in English Canada." The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, edited by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker, vol. 2, Oxford UP, 2009, pp. 602-628.

"Neith." The New Freeman, 7 Mar. 1903, p. 7.

Spray, W. A. The Blacks in New Brunswick. Brunswick Press, 1972.

Williams, Dorothy. "Print and Black Canadian Culture." History of the Book in Canada. 1840-1918, edited by Fiona A. Black et al., vol. 2, U of Toronto P, 2005, pp. 40-43.

Walker, Abraham Beverly. "Editorial Announcements." Neith, vol. 1, no. 1, Feb. 1903, pp. 59-60.

---. "Editorial Announcements." Neith, vol. 1, no. 2, Mar. 1903, pp. 97-100.

---. "Hayti and its Enemies." Neith, vol. 1, no. 1, Feb. 1903, pp. 2-3.

---. "Neith is Canadian." Neith vol. 1, no. 2, Mar. 1903, p. 1.

---. "The New Freeman." Neith, vol. 1, no. 2, Mar. 1903, pp. 63-64.

---. "Prefatory Remarks." Neith, vol. 1, no. 1, Feb. 1903, p. 1.

---. "A Special Note to Our Friends." Neith, vol. 1, no. 5, Jan. 1904, p. 199.

---. "Tillmanism, or Mob Rule in the South." Neith, vol. 1, no. 1, Feb. 1903, pp. 16-22.

Walker, Julian H. "The Once and Future New Brunswick Free Press." Journal of New Brunswick Studies, no. 1, 2010, pp. 64-79.

Winks, R. The Blacks in Canada: A History. 2nd ed., McGill-Queen's University Press, 2014.